Many, many years ago when I was still on Facebook, someone posted a poll asking if Eric and Dylan are heroes. This is a common topic in Columbine-centered groups, and it’s a perfectly valid conversation.

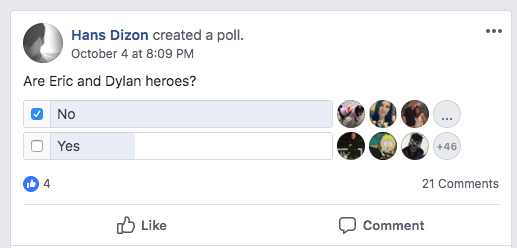

Here’s a screen shot of this poll:

As you can see, my answer was “No” and you can see my profile picture with my dog in a pink sweater. Just stating the obvious in case someone decides to twist my words here.

A couple years ago, someone posted another poll in a Facebook group asking, “are Eric and Dylan murderers or heroes?”

This seems like a pointless, opinionated poll. Who cares how people respond? However, the question itself poses two significant problems. [Watch out – here comes a Long.Ass.Post!]

[Problem #1] Asking if they are “Murderers or Heroes” implies that killing people has the potential to be a heroic act, and when that’s so, it doesn’t count as murder.

Assessing murder as a heroic act (or not) is entirely subjective, and there are only two general groups of people who would consider Eric and Dylan heroes.

The first group consists of people who are misusing the word “hero” in order to make a controversial statement that pisses people off from the safety of their bedrooms. You know, shit disturbers.

The other group consists of people who honestly believe the victims deserved to die that day. This can include people who fully understand they didn’t target people they hated; this group of people agree with killing everyone and don’t believe anyone is truly innocent because they hate humanity.

Defining “Murderer” and “Hero” would eliminate the question all together and reveal it to be no question at all, but a thinly disguised attempt at garnering the agreement and support of people who do consider Eric and Dylan heroes.

Nobody who thinks otherwise would ever pose this question in this way, and certainly not in a poll. [By now, the OP has probably friended everyone who said “hero” or “martyr” or called Eric a “God.”]

[Problem #2] Asking if they are “Murderers or Heroes” causes people to choose one over the other on conscious and subconscious levels. Sometimes the choices won’t be the same. For example, someone who is wrestling with their ability to identify with the shooters might subconsciously choose “heroes” while consciously choosing “murderers” (because that’s what’s “right”) and this will create cognitive dissonance for them.

Neither choice will sit quite right with them on a conscious level. They’ll feel torn. Rolling this question around in their mind will also potentially drive them further into seeing them as heroes because in order to see them as murderers they will need to let go of their identification with them. If they aren’t ready to let that go, then they’re going to stick with “heroes” because it preserves their own self-image and identifying with Eric and Dylan is probably the center of their world.

The question “are they murderers or heroes?” is a loaded question that forces a person to choose between acknowledging an indisputable fact (they are murderers) and embracing an ideology (they were heroes). You can’t pit a fact against an ideology and have a fair question. It’s like saying, “would you like to eat your pasta with a fork or a zebra?” Or, “do you think Jeffrey Dahmer was a serial killer, or a hero?”

The biggest problem? Those who read this question and embrace the ideology (they were heroes) automatically become at odds with facing the fact that they were murderers. They can’t see both because it’s an either/or question. The question is deeply problematic. It’s a leading question that divides every single person who reads it, even if they don’t reply or take it seriously.

What makes it worse is people have existing associations with what a “murderer” is (lowlife, scumbag, freak, loser, degenerate, evil, etc. then add in all of the opinions they’ve formed while growing up) and because of that existing association, anyone who can identify with Eric and Dylan will be triggered (subconsciously) by the use of the word “murderer” in a negative way. They can’t admit that they are murderers because they equate murderers with (insert negative association here). They equate murderers with scumbags, people who are losers, idiots, etc.

This is why it takes so long for people to come out of the space where they view Eric and Dylan as heroes. The way we discuss the case keeps people in an either/or exclusionary world. That is a dangerous world to live in.

When someone can identify with Eric and Dylan, they can’t acknowledge that they are murderers (scumbags) because that would mean they, themselves, are scumbags.

Questions like this one drive people further into denying the terrible crimes of murder Eric and Dylan committed because it’s an either-or question that pits two options against each other that aren’t either-or options.

It seems like I’m picking apart the question for no good reason, but I’m not. The way people dialogue and converse about incidents like Columbine directly shapes how they continue to view the incident, their world, and shapes how they live their lives.

Our language creates our world and our life.

The question, “Murderers or Heroes?” would never cross the mind of someone who doesn’t admire their actions in some way. Someone who doesn’t consider them heroes would never think to ask people to choose between a fact (they killed people) and the ideology of heroism.

The way we view the world lives in the language we use to describe the world.

What we say shapes everything we experience. One tiny word can close us into a narrow, limited box and we won’t even have a clue that we’re trapped.

For instance, most live in an exclusionary “either-or” world, where they say things like, “I’d like to go to your party, BUT I have to study.” The word “but” leaves no option to do both. The person really believes they must choose between studying and going to the party because they use language that only allows for choosing one over the other.

You could say, “nonsense, they can do whatever they want!” but when you really look at how you speak, and the words you use, you’ll see that your actions follow your words, not theoretical possibilities. And declaring that BUT puts you in a position with zero options other than choosing the party over studying, or vice versa.

The word “but” creates stress when making your decision. It creates the need to weight the pros and cons. “Here are all the reasons I should go to the party instead of studying.” “Here are all the reasons I should stay home and study.”

There’s no room for any other decision-making method in an exclusionary universe where it’s this or that. That’s a serious loss of power.

Living in an inclusionary universe where it’s this and that removes the stress, limitations, and opens up possibility.

“I’d like to go to your party, AND I have to study, so let me figure out a plan.”

You couldn’t even think about figuring out a plan when you said “BUT I have to study.” The word BUT puts an end to all resolutions and possibilities.

And so it is with the way Columbine is discussed… language is everything. The words used, the way questions are formulated, everything, shapes what and how you see Columbine and yourself through that lens…

It’s simple, but not easy.

In an exclusionary, this or that universe, someone might say, “I want to acknowledge that they are murderers, but I understand why they killed, and I can’t reconcile the two.”

There’s no need to reconcile anything. They are murderers and some people understand why they killed. These two facts can co-exist. The original question (are they heroes or murderers) is unfair, leading, and loaded.

The original question is a setup. It’s a question that suggests it’s optional to believe in a fact (they are murderers).

A fair question for discussion or thought would be, “are they heroes or cowards?” Or, “were they justified in their murders?”

Discussing a dichotomy of ideologies (hero/coward) is purely subjective, but at least it’s a fair discussion.